Discover the beauty of the night

Getting out at night in the quiet is one of the high points of the winter backpacking experience. The snow reflects the moonlight and the winter nighttime landscape becomes radiant. When the moon is gone, the Milky Way arches across the sky. Most of the seemingly endless number of stars are merely the ones visible to us within our galaxy. You will find that the night can provide some of our deepest and most memorable wilderness experiences.

The more you go out at night the more you will fall in love with the experience.

Winter nights are long. I usually sleep twice. Most hikers go to bed early or shortly after dark during the winter months, which can be as early as 6–7 PM. For that reason, I always make a point of getting up in the middle of the night and walking around under the stars. If the moon is out, the snow will be lit up and the features of the landscape are visible and uniquely beautiful.

Because I’m usually alone and there is the danger of tree wells and snow bridges, I don’t go far and I usually walk mostly on the tracks created during the day. Quite often I will make a hot drink or, if it is a cold single-digit night, reheat my hot water bottle. The time it takes to get on my snowshoes, jacket, and gloves is a minor inconvenience given the rewards of the night. In total, I typically spend one and half hours out in the middle of the night if I cook a small midnight meal.

If you are warm in your sleeping bag, getting up at night is much easier. If you are cold and huddled in your sleeping bag, you will not want to get up and you will miss out. Bring the appropriate gear and use the necessary winter techniques so you can enjoy the full beauty of this winter experience.

Try sleeping with your tent door open

Another way I maximize the benefits of the winter night is to leave my tent door open. Whatever the temperature, I always bring the gear required to stay warm with my tent door open. This is mainly so I can see the view and stars whenever I wake up at night. I also enjoy the first rays of the sun on my face in the morning. Provided it is not too windy or snowing outside my door will always be open.

Three benefits of leaving the tent door open

Besides the stary night and young Dawn with her rose-red fingers as Homer referred to the sunrise, there are three additional benefits to leaving your tent door open:

- Safety: Leaving the tent door open provides some additional safety, because you can more readily perceive the approach of thunderstorms or interpret whatever is making noise outside your tent or around camp.

- Small mammals: This practice of leaving the door open also means that small mammals (especially mice) can come and go in their search for food without having to eat a hole through the tent. However, mice have eaten through the foot of my sleeping bag to remove down for their nest. I expect they would have torn through the tent too if it was sealed up.

- Less condensation from your breath. An open tent door means your gear is less likely to get damp or covered in frost. If your tent has an end door, sleep with your head there. This will put your head under the stars and reduce condensation in the tent.

These benefits are, of course, contingent on no wet clouds, snowfall, or winds carrying snow drift.

Not about toughness

I don’t sleep with my tent door open because I can endure the cold or like being cold, but rather because my sleeping system provides the warmth I require. If I were cold, I wouldn’t leave my tent door open. Being warm while you sleep is important for your safety and wellbeing.

As long as my body is warm and my blood has good circulation, I’m comfortable. I don’t even need a balaclava to protect my face from the cold. My face is warm enough. Temperatures below 8000 feet in the Cascade Mountains are rarely below 0ºF, so closing the tent door to add 5–10 degrees of warmth is not necessary. I can stay warm in my sleeping bag so don’t need any extra warmth. This means I am not camping at the limit of my gear’s abilities. I try to use a sleeping bag that is 10–20º warmer than the forecasted temperatures. However, if the weather is colder than expected, I can add extra warmth by closing the tent door.

You may be wondering, why not completely forego setting up the tent on clear nights? I’ve been tempted many times, but there is usually a gentle breeze in the night which will gradually robe my sleeping bag of warmth. While I like having my door open I also like having the overall wind protection provided by the bottom edge of the tent. And, I don’t want to lose any gear to an unexpected gust of wind. It is not unusual to experience unexpected high winds just before sunrise.

Organize your gear for getting out at night

Make it easy for yourself to get up and enjoy the night. When I get in my sleeping bag, I have my headlamp nearby. My boots are in a dry-sack or plastic bag and placed inside the tent next to the sleeping bag or, if there is single-digit cold weather, placed inside my sleeping bag. My gloves and mittens are inside my sleeping bag so they are already warm when I want them. Snowshoes are closeby outside the tent stuck in the snow in a vertical position so they are easy to find when it snows. All food is in a bear-proof container outside the tent. I usually keep my camp layers (base layer, down pants, and rain pants) on my legs and my puffy jacket inside my sleeping bag so I can get ready and go out quickly if someone needs help.

Stargazing has a way of putting life into perspective like few other experiences. All the more so because recent discoveries has given us a better idea of our place in the universe. I hope every winter backpacker can master the cold so well that it doesn’t prevent them from going out at night and enjoying this experience.

Stargazing for Beginners

In ancient times, life and the stars were deeply connected. The night sky provides a practical calendar and a clock, a means of orientation and navigation, and a source of wonder. Our myths, religion, and politics, as well as our fears and hopes, were interwoven with the stars and celestial phenomena. Even our biology is shaped by these celestial objects. The composition, gravity, tilt, and spin of the earth; the lengths of the days and nights, the orbit of the moon, and the changing of the seasons, all effect us—from the density of our bones to our sleep patterns and moods. We are literally made from star dust and fine-tuned for our cosmic environment.

Today, most people are cut off from the stars because of urban lights. But out in the wilderness, there are still places where we can easily observe the stars, constellations and asterisms (obvious star patterns), the Milky Way, planets, and meteor showers, as well as the rarer appearance of comets, auroras, lunar eclipses, and planetary conjunctions. We can also see aircraft lights, satellites, and space stations orbiting the earth. Science has revolutionized our understanding of the night sky but has not diminished the wonder. The sky spreads out before us a window to a universe far larger than anything our ancestors could imagine.

Five things to do to connect with the night sky

Before beginning, turn off all lights and headlamps and allow your eyes to adjust to the dark. These explanations are based on the Northern Celestial Hemisphere.

1. Orient Yourself with the North Star

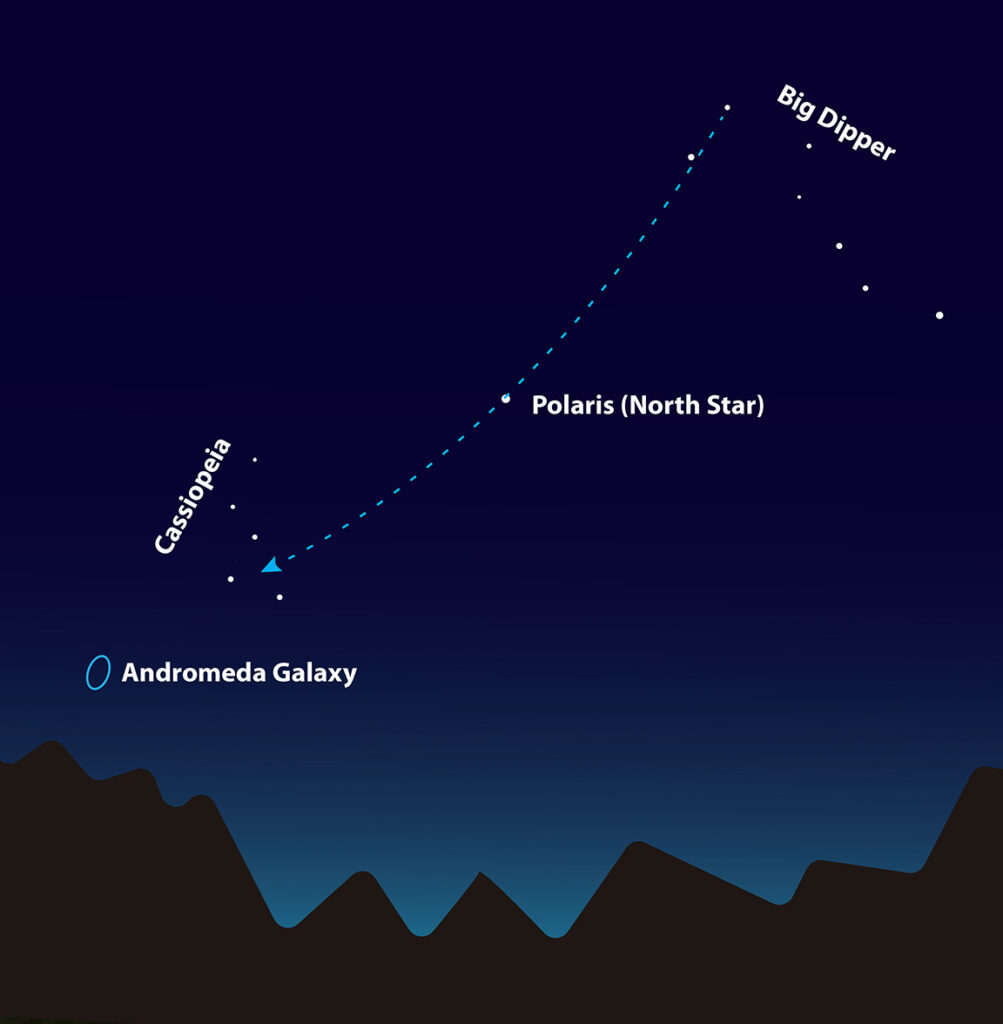

The North Star, also known as Polaris or the Pole Star is the star directly above the North Pole or Earth Axis. It can be found by first locating the “Big Dipper,” also known as The Plough. The Big Dipper is not a constellation, but rather an asterism (an obvious pattern of stars). It is situated in the constellation Ursa Major, the Bear (oddly, drawn with a tail). You can learn about that later. For now, focus on the Big Dipper. Find the two stars at the end of the dipper (not the handle) draw an imaginary line from the bottom star to the top star and continue from there to the next bright star. That star is Polaris. It is also the star at the end of the handle on the little dipper (also the constellation of Ursa Minor or Little Bear).

When you face Polaris, you are looking north. South is behind you, east is to your right, and west to your left. You have now oriented yourself and determined the cardinal directions. This celestial marker will remain the same all night, everynight, providing your essential orientation. Look at the horizon and notice the position of the North Star in relation to the nearest peak. This will help you navigate. All the other stars will move counter-clock-wise around Polaris as the night progresses and the Earth rotates. Becoming aware of Polaris and the seeming movement of the stars reminds us that we are situated on a spinning speck in a vast universe.

Ancient navigators could use stars to find their way because stars and constellations follow recognizable paths with some rising and setting at particular times of the year and specific spots on the horizon.

Navigating with the Stars

Around 2700 years ago, Homer’s Odyssey tell the story of Odysseus using the stars to navigate home. This is the oldest account of celestial navigation.

“The wind lifting his spirits high, royal Odysseus spread sail—gripping the tiller, seated astern—and now the master mariner steered his craft, sleep never closing his eyes, forever scanning the stars, the Pleiades and the Plowman late to set and the Great Bear that mankind also calls the Wagon: she wheels on her axis always fixed, watching the Hunter, and she alone is denied a plunge in the Ocean’s baths. Hers were the stars the lustrous goddess told him to keep hard to port as he cut across the sea.” —The Odyssey, Book V, (Fagles’ Translation)

In this passage, the goddess Calypso tells Odysseus to keep left (“hard of port”) of the Bear constellation (Ursa Major) as he sails from the island of Ogygia across the sea in search of Ithaca. Which is to say, go East. Using the recognizable celestial signs given by Calypso, he can maintain his direction East without a compass (and without the North Star that we would use today).

The bear “wheels on her axis always fixed”—meaning, the dark spot above the Earth’s axis around which all the stars revolved. In our time this axis points to the North Star but back then it was just a dark spot in the sky. That»’s why Calypso didn’t point out the North Star. 2700 years ago, the “axis fixed” wasn’t a bright star. Over time, the axis changes due to the precession of the equinoxes. That is, over centuries the declination changes slightly and the “fixed” axis is no longer pointing to the same spot.

She (the bear) is “watching the Hunter,” also known as the constellation Orion. This indicates that the bear is the Big Dipper (big bear) and not the Little Dipper (the small bear). “She alone is denied a plunge in the Ocean’s baths” refers to the fact that the Bear is visible throughout the year and doesn’t dip below the horizon like Orion, the Plowman, and many other constellations. Remember, the Big Dipper is a asterism situated in the Big Bear constellation (Ursa Major). To find the Plowman (also called “Boötes”), follow the arch of the Big Dipper’s handle to the bright star (Arcturus, brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere) that looks like it is the lower part of a star configuration in the shape of an ice cream cone. This cone shape is the Plowman constellation.

2. Find the Ecliptic

Long ago some people thought the sun revolved around the earth because that’s what it appears to be doing. The path it follows in the sky is called the ecliptic. All the planets roughly follow this same path. Notice the path of the sun during the day because that’s going to roughly be the same path for the moon and planets at night. It is higher in the summer and lower in the winter because of the tilt of the Earth.

The ancient Greco-Roman astronomer, Ptolemy, listed 48 constellations. The modern list includes 88. The Ecliptic passes through 12 of these constellations and these twelve are known as the Zodiac. Knowing where the ecliptic is situated will help you distinguish planets from stars and locate specific constellations. It will also allow you to gauge the location of the sunrise and moon’s setting. Knowing the path of the moon will help you determine when you can wake up to view the stars without the interference of moonlight.

Over time you will also notice that the position of the inner planets (Mercury and Venus) change rapidly whereas the farther observable planets (Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter) move gradually. If you observe the outer planets long enough you will notice the retrograde motion of these objects. Referring to this Ptolemy wrote: “When I trace at my pleasure the windings to and fro of the heavenly bodies, I no longer touch the earth with my feet: I stand in the presence of Zeus himself and take my fill of ambrosia, food of the gods.” (Almagest Book I).

3. See the Milky Way

One of the great thrills of being out in the wilderness on a dark night is seeing the Milky Way. The brightest core of the Milky Way appears near the horizon behind the Scutum and Sagittarius constellation in the late Spring to early Fall. During the winter, the fainter portion crosses the sky behind the Gemini, Auriga, Perseus, Cassiopeia, and Cygnus constellations. It is not as bright in the winter but still noticeable and beautiful to see.

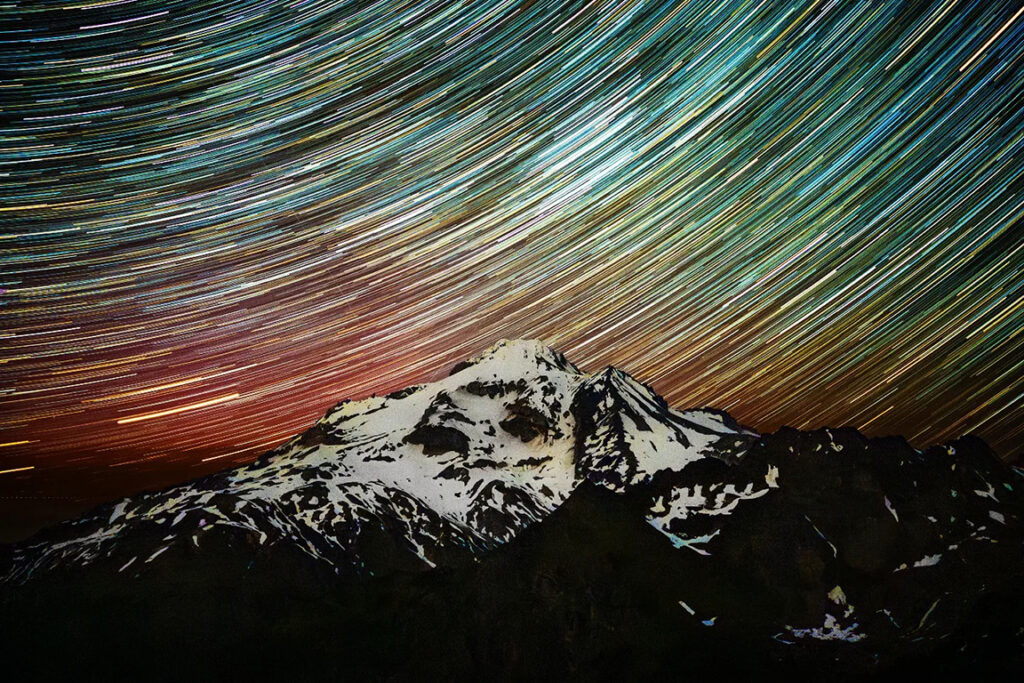

A light pollution map will show that Washington State has a significant amount of light pollution, although not nearly as much as the East Coast. This light pollution makes the Milky Way less bright but it is still visible from many of the wilderness areas and national parks in the Pacific Northwest. Look for the Milky Way on new moon nights or when the moon is below the horizon. From the North Cascades to Mount Adams you can see the Milky Way on dark nights. The ability of our eyes to see stars depends on the amount of light our eyes can collect. This is why long-exposure photographs capture far more stars and light than we see with our unaided eyes. Without a lens, our eyes can only see a few thousand stars. The 100 billion farther stars of the Milky Way appear to us as a cloud-like shape across the sky because it contains so many far-away glowing stars.

The name “Milky Way” comes from a Greek myth that Hera, wife of Zeus, spills milk while breastfeeding. In many cultures it was seen as a heavenly path. The Lakota people of North America thought of it as a spirit trail to a place of many lodges. Among Christians in Europe, some thought the Milky Way was the path of souls to heaven. In Spain it is called El Camino de Santiago, literally, the pilgrimage “road to Santiago.” In medieval legend, the Milky Way was formed from the dust raised by traveling pilgrims on their way to Santiago de Compostela. Thanks to large telescopes we know the Milky Way is a vast number of stars forming part of our galaxy.

4. Look Beyond the Stars of Our Galaxy

If you can spot the Great Galaxy of Andromeda, you have seen an object beyond our Galaxy. The Andromeda Galaxy (also known as M31 or commonly called “Andromeda”) is situated by the Andromeda constellation. One way to find it is to locate the constellation of Cassiopeia, which is composed of five bright stars that make the shape of a letter “W.” Find the Big Dipper and imagine a line from the end stars to Polaris and now continue about half the same distance to find Cassiopeia. The right bottom point of the Cassiopeia “W” shaped configuration of stars points towards the Andromeda Galaxy. The distance of Andromeda from Cassiopeia is about the same as the width of the Cassiopeia constellation.

To the naked eye, the Andromeda Galaxy appears to be a faint fuzzy gaseous-looking spot in the sky. Success will depend on a dark sky and good eyesight but you should be able to recognize it as a faint dot. With a small tripod, a 30 second exposure with a cell phone will reveal a clearer image of the galaxy’s shape.

In Greek Mythology, the Andromeda constellation represents the beautiful daughter of Cassiopeia, the queen of the Levant region (called Ethiopia by the Greeks). Cassiopeia never sets in the Cascade Mountains.

It was only in the early 1920s that astronomer, Edwin Hubble, determined that Andromeda, originally thought to be a nebula in the Milky Way, was a galaxy far beyond the Milky Way. Once you locate and see the Great Galaxy of Andromeda you have looked 2.5 million light years beyond our galaxy!

5. Solve the Fermi Paradox

Once you have seen the Milky Way and peered beyond it to another galaxy containing a trillion stars — you will no doubt have a sense of the immensity of the Universe and relative smallness of our home, planet Earth. To physically confront this reality with your own eyes is in itself is a profoundly existential and sublime experience.

With so many stars and possible planets in the Universe, scientists have wondered about the discrepancy between the lack of evidence for advanced extraterrestrial life and the high likelihood that it exists. The problem of this great interstellar silence is known as the “Fermi Paradox” named after the physicist Enrico Fermi (1901–1954).

The proposed solutions typically involve arguments that such life is either rare, undetectable for various reasons, unable to survive its self-destruction, disinterested in our planet, or hiding for fear of interstellar predation.

What do you think?

Contemplate this question as you look up at the night sky: Are we alone? Which is more thought-provoking, the idea that advanced life in the galaxy is abundant or that in this vast universe, we might be alone?

You can read more about the science and history behind this debate at this link: Fermi Paradox.

The contemporary belief that life is abundant in the universe is based on scientific data. In the 1500s, Giordano Bruno used theology to conclude that other worlds existed with animals and inhabitants. The Inquisition disagreed and found him guilty of heresy and he was burned at the stake in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori in 1600. A statue memorializing him was erected on the same spot in 1889. Thankfully, we can contemplate these topics today without taking such risks.

Resources for Stargazing

There are a number of easy to use free Apps, websites, and inexpensive published guides that will help you plan trips and make accurate observations without the need to go into full-on geek mode.

Stargazing Apps

Star Walk 2, Night Sky, SkySafari Astronomy, etc. are among the popular free stargazing Apps. I have only tried SkyView Lite and Stellarium. The Lite version of Skyview is free and doesn’t contain any ads. The paid version of the app costs $1.99 and counts more stars, constellations, and other space objects. I use the Lite version as it is sufficient for basic observations, learning the constellations, determine where the sun and moon will rise among the peaks, and for identifying other space objects.

Websites

TimeandDate.com is a website that will show the current status of the sun and moon, such as phases, times for rising and setting. You can set it for specific locations (nearest city). It also provides status on the visibility of planets. Stellarium-web.org will give you a larger view of the night sky on your desktop, but it is also available as a free opensource App for phones. It allows you to set the date and time.

Printed Guides

If you prefer a printed guidebook, a useful resource is the annual Guide to the Night Sky published by HarperCollins (USD $6.99). They publish an edition specifically designed for North America. It is useful to beginners and experienced stargazers. Cambridge University Press publishes The Monthly Sky Guide by Ian Ridpath—a beginners guide to all the main sights of the night sky.

Have any questions or comments?

In the comment section below, let us know your thoughts. Your comments and questions are welcomed.