Begin by Building a Team Mindset

Some backpackers and hikers are introverts who like their solitude. As an organizer, you want to get everyone to respect the group and be a team player. This will increase safety. There are specific things you can do to build a team mindset.

- First, create a group structure. Emphasize that it is a group event. Designate a navigator to lead the group and a sweeper to check on anyone in the back who is slower or having difficulty. Having a navigator and sweeper helps create a group structure. The navigator is usually the first person to observe challenging conditions on the route. When this happens it is important for the navigator to discuss options with the sweeper. The sweeper is the person who has the best observations about those in the group who might need help navigating the route.

- Second, keep people together. This will help them get to know each other. People care more about people they know. They become more patience and more helpful when the person slowing down the group is a friend. The key is to stay together—ride together, hike together, eat together, and camp together. There is always time around camp for people to wander around and have solitude.

Carpool together, hike together, eat together, camp together

- Carpool together. Have a designated gathering point such as a Park and Ride. From there, people can carpool to the trailhead. People often have more time to chat and get to know each other during the drive than during the hike.

- Hike together: This is the hardest thing to do in cold weather. People need to maintain a sufficient pace to keep warm and not everyone has the same pace. Nonetheless, set expectations at the start of the hike. Get faster hikers to stop and layer up, if necessary, at points along the way. Have a lead navigator and a sweeper to hold the group together.

- Eat together. If the drive to the trailhead is long, try to have a place to stop for coffee and a restroom break. At the campsite, dig a cooking pit in the snow. This provides a place for everyone to sit together at meal times. I usually dig a C-shaped pit for the whole group while everyone sets up their tents. This shape allows everyone to see each other during meals. This is an important practice because it helps ensure that everyone gets a hot meal, their water resupplied, and a hot water bottle for the night. It also allows you to see how everyone is doing or if there are any issues that need your attention.

After the hike, find a restaurant where everyone can have a meal together before returning to the Park and Ride. Often, the food options are limited and subpar but I can usually find a pizza place or a Mexican or Thai restaurant that can accommodate most people including vegetarians and those with halal restrictions.

- Camp together. Left to themselves, some hikers will walk off and set up their tents away from the group. Encourage everyone to camp fairly close together. This is important for safety. In a storm, the wind makes it hard to hear people in trouble. If you need to get everyone to break camp and move off an exposed ridge because of a sudden lightning storm, you want everyone close by. Any gear or warmth problem is easier to manage when you can communicate with the group.

Ultimately, your winter backpacking group is an opportunity for people to make friends. As you get to know people in the group you can help facilitate these friendships.

Encourage Self-sufficiency

It might seem contradictory to the goal of team building, but gear sharing is not the safest practice when it reduces gear redundancy. In winter conditions, gear redundancy, and gear self-sufficiency are important.

- Gear redundancy: First, if a stove fails, someone else can offer theirs as a backup. If the whole group is relying on one or two stoves and they fail, it could create a serious safety issue. If an air mattress fails, another hiker can share a solid pad (combined, two pads are 4 R-value). If a tent blows away, someone can share their tent.

- Gear self-sufficiency: If someone gets ahead of the group and gets lost, gets separated from the group in a whiteout, or decides to turn back, they need a complete gear set to be safe. If you plan to share a tent and that person doesn’t show up for the event, what will you do? Everyone should have a complete gear kit. They should arrive self-sufficient, know the route, and be ready to navigate safely.

Have a Liability Release

Liability is a serious concern. Having a liability release helps draw attention to the risks involved and that awareness will help encourage attendees to pack and behave responsible. For every event, I post a Release of Liability in the event description and I request an acknowledgment that participants are releasing the organizers from liability. Everyone is informed in the Welcome Letter that joining the Meetup means that they are accepting of the Release of Liability.

- I avoid charging or accepting any payments because that may be interpreted as indicating a fiduciary duty.

- Everyone is responsible for themselves and for knowing the risks they are accepting.

- Never understate the dangers or risks involved.

- Never characterize a route or activity as “safe.” Any hike into the mountains, any time of the year, involves hazards that could result in injury or death.

- Encourage people to join, but make it clear that the dangers and hazards are real and are part of the experience.

Leaverage Diversity

The goal is to increase safety by building a team and that’s easier to do if you have an inclusive mindset and strategy. It is best to set aside assumptions about who will be interested in winter backpacking or capable of doing it.

When it comes to carrying a heavy pack up a mountain, I have not found that large men are better at it than small women. Often when I post a difficult hike, it is mostly women who sign up. Some members are experienced mountaineers and others are office workers just discovering outdoor recreation.

Neither gender nor age are indicators of ability. Many of the strongest and most capable hikers in our meetup are small and in their 50s and 60s. Many of the slower hikers are better able to reach the destination on longer routes. The general guideline is that a backpack should be no more than 20% of a hiker’s body weight. For the smaller hikers in our group, it is closer to 30%. You cannot judge a person’s abilities or commitment by appearance.

My own observation is that Meetup groups that are more inclusive tend to have more participation and longevity.

Creating a safe and welcoming Meetup experience is not difficult. Here are a few basic tips that will help everyone benefit from the group experience:

- Avoid gender assumptions.

- Avoid comments about a person’s appearance.

- Avoid comments and jokes about sex and sexuality.

- Don’t over-explain. Before offering advice, consider prefacing it with “I would like to offer some advice but I don’t want to be explaining something you already know.” They will appreciate the respect and usually indicate whether you should proceed.

- Let people take care of themselves. Don’t touch or give physical assistance unless it is requested.

- Have a three-person minimum.

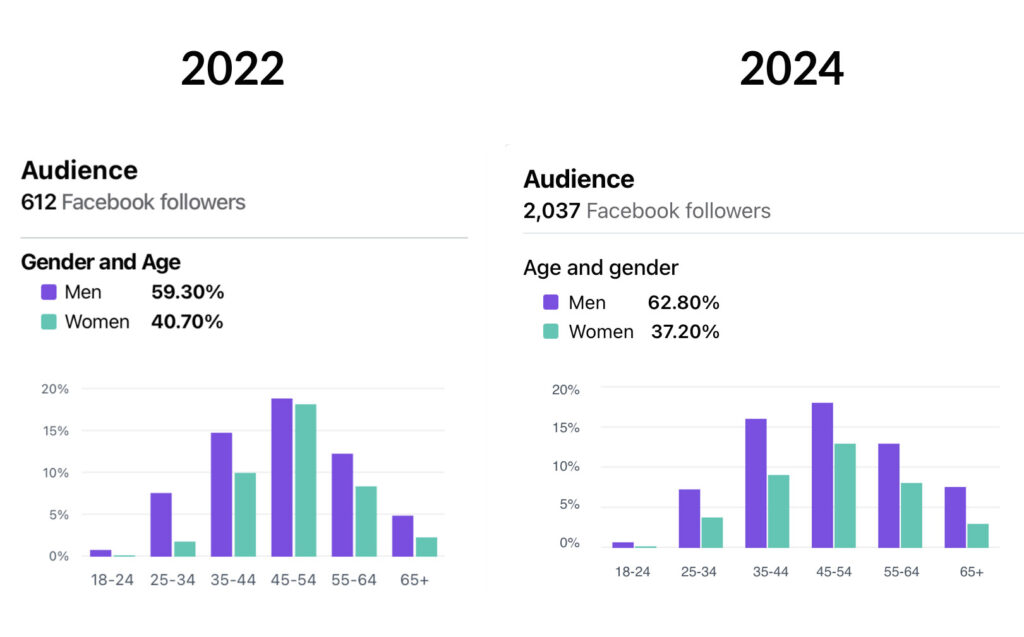

Some of our events are majority-male and others are majority-female. The membership stats for our Facebook Group page are about 60/40 male/female with the largest number of hikers in the 45–54 age demographic. For some reason, it seems that people are more adventurous in that age group.

Friendships

In 2019, my closest friend and teenage hiking buddy passed away from a heart attack in his sleep. I have thought much about the value and importance of friendships following this loss. In particular, how our backpacking group can help people discover and build friendships through shared experiences. Friendship can be an important source of joy and support in the course of our lives. The best kinds of friendships are the ones that encourage us be our best selves.

Are you familiar with the Harvard Study of Adult Development? It is the longest in-depth study on human life ever done, with the researcher concluding that good relationships is the most important thing leading to health and happiness. “The trick is that those relationships must be nurtured.” The current directors, Waldinger and Schulz authored a book based on the findings, The Good Life: Lessons From the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness (2023). The book presents the research findings and also contains tips for maintaining relationships. For example, they discuss how we may withdraw from others or lash out when conflicts arise in relationships. “Neither of these are ideal ways to manage stress or anger, as they aren’t focused on preserving closeness or working through difficulty.” The authors suggest that, “The key is … a more considered and purposeful response that aligns with who you are and what you are seeking to accomplish.” They point out that this can help you be less reactive and give you a better chance of working through issues. And what are we seeking to accomplish? Friendships.

Seattle, like most American cities, is a diverse place with people from around the world. This diversity is reflected in our Meetup group. We have hikers ranging from early 20s to mid 60s from China, Taiwan, India, Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Latvia, Israel, Syria, Iran, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Germany, France, Netherlands, and more. Thankfully, the people who join in our activities are openminded and accepting of diversity.

Many are already experienced backpackers and others are new to the activity. People from every background enjoy winter backpacking. Don’t assume any particular ethnicity, gender, or age group will not be interested in winter backpacking, capable of handling the challenges involved, or unable to be your friend.

People are individuals and everyone loves the wilderness in their own way. My own experiences with winter backpackers has confirmed my belief in the fundamental oneness and goodness of humankind. I am grateful for all the people who have joined in on these wilderness adventures.

Ask for Help

Hiking groups often split into fast and slow hikers. New hikers can struggle with balance in deep snow and are sometimes filled with anxiety and fear making mistakes or being left behind. As an organizer, it is hard to look after new hikers, slow hikers falling behind, new hikers getting too far ahead and also keep the group together, and be upfront navigating to the planned destination.

If you can identify a person who can assist you with the organizing, it will make it easier to keep the group together. Enlist a capable hiker to help you. Someone who will help you reign in the ones that want to take needless risks. Explain that you want them to consult with you and help keep the group together. Be encouraging. Two heads are better than one. It is good to give everyone a voice in the group, but ultimately, decisions need to be made. If you can make the decisions with another respected hiker in the group, it is easier to maintain group unity and safety.

Prioritize Safety

Winter backpacking in groups is safer than going solo. Groups are a great way to share knowledge and practice safety skills. If you are starting a group, be aware of the hazards and gear requirements, some of which may be unique to your destination and weather conditions. The trails are often hidden under snow along with streams, frozen ponds, and tree wells.

- Everyone should have avalanche gear and beacon recovery skills while exploring mountainous terrain.

- Use routes on slopes anchored with trees and rocks. Make ascents on approaches with less than 20–25º inclines.

- Choose campsites in open spaces away from snow-loaded trees or slopes.

- Pack a kit that doesn’t require fires for warmth and exceeds the demands of the weather forecast.

- Have wind-protecting gear to prevent hypothermia and frostbite.

- Pack in gear redundancy and ensure everyone is self-sufficient if separated from the group.

These are just a few important safety considerations. With the appropriate gear and skills, winter backpacking can be a comfortable, unique, and amazing experience.

Vetting Members

Vetting members is challenging. Some people will sign up who lack the basic fitness, skills, and gear to participate. Some will bring backpacks that are too heavy for them to carry. Some cannot balance on snowshoes nor have the strength necessary to break trails. For this reason, when people request to join, I ask them two simple questions:

- What is the most difficult hike you have hiked recently? and

- Do you carry the ten essentials?

The answers people give provide an idea of their abilities and skills. If someone says they don’t know about the ten essentials or don’t carry them, you can encourage them to get more experience and skills before joining the winter backpacking events.

Beware of people whose most difficult experiences are to places where they relied on tour guides. They may expect you to take care of them.

Create a Measure of Fitness

For difficult trips, it is good to have some way people can measure their level of fitness and readiness. In the Seattle area, there are many nearby trails of similar difficulty, such as Mailbox Peak (9.4 miles round trip and 4,000 feet of elevation gain) and Mount Si (8 miles round trip and 3,150 feet of elevation gain). Most everyone in our area has hiked these trails. The Washington Trails Association website says this about Mount Si, “Gaining 3,100 feet in a little under four miles, it falls in a kind of sweet spot for experienced and novice hikers alike: enough of a test for bragging rights, not so tough as to scare people away. In early spring, climbers getting ready for Rainier come here with weighted packs. Conventional wisdom says if they can reach the end of the trail in under two hours, they’re ready to conquer the state’s tallest peak.” For our events, if a person can complete the Mount Si trail with a full pack in around three hours, that is good enough.

Some people will decide the group is too challenging or not challenging enough. Participants need to have similar abilities or a willingness to accommodate their differences.

There will be people who show up unprepared. Some people don’t read the event information and gear requirement notes and some will not agree with or respect your advice and planning. You can do a few gear checks to understand whether a person is paying attention.

In some ways people who are new to backpacking adapt more quickly than experienced 3-season hikers who are set in their ways and gear choices.

Encourage gear checks

There are three types of gear checks:

- Individual gear checks: These checks should be done by each member of the group when they are packing their packs. Ideally, this check should be a visual check using a checklist, such as laying out the gear on the floor or a table and checking off each item. Equipment should be checked for damage, especially snowshoes, transceivers, and headlamps. Liquid-fuel stoves should be periodically serviced.

- Meetup checks: This check is done wherever the group plans to meet before carpooling to the trailhead. It is unrealistic to examine everyone’s pack before an event. However, if you recommend helmets and people show up with no helmets, it lets you know who is taking your advice seriously and who is not. I usually only check a few obvious things:

- Transceiver: Even if they can’t use it properly, they should be wearing one. At the bear minimum, you can turn it on for them and at least you can find them if they are buried in the snow.

- Snowshoes: Are they mountain terrain or flat terrain? This is visually obvious. If they have flat terrain snowshoes and you know the route will be over steep slopes and hard snow, you want to advise them to come back another time with the correct snowshoes.

- Trekking poles: Some people prefer to hike without trekking poles but in deep snow with a heavy pack, they will likely be unable to balance. Trekking poles also need to be fitted with snow baskets to provide support in fresh snow.

- Solid pad: Some people think their air mattress is sufficient because it may have more than enough R-value. They don’t realize a solid pad is also needed around camp and as a backup for air mattress failures. This gear ommission is often deliberate because they don’t yet understand the need or the gear redundancy strategies used by the group.

- Nalgene bottle: For safety reasons, water should be carried on the outside of the winter backpack. The bottle should also be clipped on to secure it. Some people insist on using a pack bladder in winter. They don’t understand that this is dangerous and likely to freeze, making it useless. A Nalgene bottle is essential for comfort and first aid. Both of these issues are easy to spot without opening a backpack.

3. Trailhead check: This check specifically concerns transceivers. This is the point where everyone should turn on and test their transceiver. Hopefully, everyone has already checked their transceiver before getting this far. The point of this check is to make sure everyone is wearing it properly and has it turned on to the transmit mode.

I usually pack extra gear in my car to solve some issues, such as people forgetting items. If you see a person getting too many basic things wrong, you know to ask more questions before heading out together. Be aware that some people will consciously ignore a gear recommendation when they don’t understand why it is necessary.

Direct Message New Attendees

If a person is new to the group, it is best to reach out to them before the event and discuss gear basics. Ask them questions and see if they are responsive, argumentative, or resistant. This direct message discussion will allow you to give them a heads-up about what to bring and expect. It will also help you know if the person is adding useful skills to the group or will be a problem. The questions I ask are:

- How heavy is your pack? A pack that is under 25 lbs is a likely indicator that the hiker doesn’t have the required gear. A pack over 40–45 lbs is also a red flag. The heavier the pack the more likely they cannot keep up with the group or will be falling over in deep snow or slipping on steep slopes. Talk to them about reducing the pack weight. Sometimes people show up with heavy backpacks without even bringing the necessary gear.

- What is your sleeping bag rating? If they don’t know, encourage them to find out and possibly upgrade or bring a sleeping bag liner to boost performance. For deep cold events, it is essential to know that members are not exceeding the limits of their gear.

- What is your gear’s R-value? They need a minimum of 4–6 R-value. Even if an air mattresses has 4–7 R-value, they still need a solid pad for around camp.

Manage Expectations

Attendees usually arrive by car or public transit and meet together at a Park and Ride. Post the Meetup point, directions to the trailhead, trail name and trail number. Provide a coffee shop or ranger station address if you will be stopping along the way. As an organizer, I direct message my cell/text number to attendees so they can contact me if they are going to be late or have trouble with directions. I ask people to show up early and we usually allow 15–20 minutes for anyone who is late. After that, they have the option of trying to meet the group at the trailhead. If drivers caravan to the trailhead, that will help prevent drivers from getting lost. I also share my InReach address.

In the Meetup event comment section, you can share weather forecasts, links to the avalanche forecast, and any special gear requirements, such as bear canisters, transceivers, snowshoes, microspikes, helmets, ice axes, etc. You can also encourage them to check their headlamp batteries, stove fuel level, and fire starters. If you anticipate hiking in the rain, snow, whiteouts, or darkness, provide instructions so they can be mentally prepared and bring the appropriate gear.

At the trailhead, emphasize that people are expected to hike together. Putting slower hikers at the front of the group can help. Have a lead navigator and a trail sweeper to manage the back and front of the team. Establish stopping points so that the lead and sweep can communicate the group’s status. Be aware that most hikers will need to stop and adjust layers within the first 20–30 minutes of the hike.

Expect Some Suffering

Even if they have all the right gear, new members will likely suffer on the first event because they don’t yet understand the skills required to prevent warmth loss. You will need to keep an eye on them. In most instances, they will observe the behavior of the more experienced members and learn what to do to stay warm and safe. They will see which gear and methods works best and they usually upgrade before their next trip.

If hikers follow best practices they will be comfortable and never shiver. However, new hikers are just learning and for that reason you need to know about the early signs of hypothermia and keep an eye on their behavior.

Let us know your thoughts and suggestions

Please share your ideas, experiences, and challenges below. Your comments and questions are welcomed.