Many backpackers have been using canister stoves for years with no problems. But once they venture into winter conditions, canister stoves can lose pressure, underperform, and fail. But how cold does it have to get to experience these problems? I’m going to explore that question as well as what to look for in canister stove systems for the best performance in cold weather. For the pros and cons of liquid fuel stoves see Why Use a Liquid Fuel Stove?

The trend among American backpackers is canister stoves. Canister stoves are lighter, boil as fast or faster, and are much easier to use. So why would anyone continue to use a liquid fuel stove? The answer is cold weather and wind. That said, some canister stove designs have built-in wind protection and fuel pressure regulators, and most canisters now use isobutane fuel that performs better in cold weather (i.e., better than butane canisters). These design improvements mean that it is now possible to use canister stoves on cold-weather trips, especially in the mild winter weather of the Pacific Northwest.

But, once temperatures drop to the teens, even the best canister stove is no longer its former self. At 11ºF the Isobutane in the canister will no longer vaporize and the stove stops running unless it can be warmed.

Quite often, when liquid fuel stoves are compared to canister stoves, the challenges of wind and cold are not fully appreciated. This can be seen in gear reviews. Take, for example, Outdoor Gear Lab’s “Best Backpacking Stove of 2020”. In their view, liquid fuel stoves rank poorly. They begin with the claim, “From windy weekend backpacking trips to frigid expeditions on glaciers, we have the info to guide you toward the best fit.”

If you are a winter backpacker, windy and frigid conditions are exactly the challenges you can expect. So why does Gear Lab give the liquid fuel stoves such poor scores in nearly every category? Their preference for canisters is so strong, that even when including liquid fuel options (the MSR Whisperlite), they choose the “Universal” model because it can use a canister. Their stove review might have been better titled “Best Canister Backpacking Stove of 2020.” So what is the problem? Turns out, their idea of “frigid” is only 46 degrees Fahrenheit:

“We [Gear Lab] did our testing in a garage at about 8000 feet, where the ambient temperature was approximately 46 degrees Fahrenheit, and the water we used was approximately 43 degrees.”

Their idea of wind speed—“a box fan blowing about 3 mph.” These conditions do not put us in the realm where canister stoves fail and liquid fuel stoves demonstrate their worth.

Cold Weather and Canister Stove Performance

To understand the problems with canister options and the advantages of liquid fuel stoves, we need to get beyond this 46º F threshold. You don’t have to be a hardcore winter backpacker to want a stove that performs well on a cold morning. Once we near freezing, there is a noticeable drop in performance for a butane canister. At 31ºF, the butane fuel canister reaches its limit. With an isobutane canister, a noticeable drop in performance happens around 11°F. This loss of efficiency begins to occur well before reaching an ambient temperature of 11°F. Vapor pressure is how the fuel keeps the canister pressurized, and at 11ºF the Isobutane vapor converts to liquid causing the pressure to drop off. This is why some stoves are designed so that the canister can be attached in an inverted position. If the canister is inverted, the fuel flows out as a liquid. For safety, this needs to be a stove designed for that purpose. (I’ll discuss this further below.)

If the weather forecast has temperatures below freezing, and especially when close to 11º F, your canister stove will likely underperform or fail. At the very least, in such temperatures, you need to take steps to keep your canister stove operational, such as warming the canister next to your body, warming and rotating two canisters, keeping it in your sleeping bag, and using a small pad to keep the canister off the snow and ice.

(Some hikers also situate the canister in a pot of water to warm it, but others believe this presents a danger if the canister is new and already full. I have no data on this question.)

Several winter backpackers I know switched to liquid fuel after struggling with canister stoves in windy conditions and temperatures that were likely around 10ºF or slightly lower. Once a stove is placed in conditions where it doesn’t work, its normal virtues are no longer relevant. Despite its flaws, in truly cold weather, the steady blue flame of a liquid fuel stove is a beautiful thing to behold. But, as I mentioned, temperatures in the Pacific Northwest are mild, so it is unusual to be out in weather so cold you cannot keep a canister stove working, even if at lower efficiency.

Canister stove manufacturers tend to avoid specifics about temperatures and instead speak in generalities such as “frigid,” and “cold weather.” I think there are two reasons. First, mentioning the 11ºF problem will scare many people away from canister stoves. Second, ambient temperature is not an absolute measure for when a stove will fail because you can warm the canister to keep a stove running. Jetboil’s website includes some interesting comments:

“All canister stoves suffer a performance drop in cold weather. The colder the fuel, the lower the vapor pressure, and the lower the burner output. As far as the fuel, the output pressure in any canister stove is governed by the temperature of the gas inside the canister. As temperature drops, so does pressure. The result can be noticeably longer boil times and difficulty lighting the burner with the built-in piezoelectric ignitor. Jetpower’s lower firing rate reduces canister cooling and increases performance. Jetpower fuel, with propane, helps to mitigate cold weather problems.”

(See “Does Jetboil Work in Cold Weather?: Frequently Asked Questions”)

So will it work in the cold or not? Based on these comments, you might think operating a canister stove in winter may not be so challenging. However, when Jetboil mentions actual temperatures, hope begins to fade:

“If you are looking to use your cooking system in temperatures colder than 45 degrees Fahrenheit, please check out our MiniMo, Sumo, and Joule cooking systems. These systems feature our advanced Jetboil Regulator Technology to deliver consistent heat output down to 20° F (-6° C).”

Wow, once you reach 45ºF you need to switch to their cold-weather canister stoves that will now deliver “consistent heat output down to 20° F.” Bear in mind that these advanced stoves are all using Isobutane and not butane. Will you get to enjoy a hot meal while taking in the Alpine views from your campsite on top of a frozen lake? Maybe not—or not without a struggle. But, if you’re using a liquid-fuel stove, it is just another day on the ice. You can fire it up and enjoy that meal same as you would on a summer day.

By itself, a canister stove will not keep functioning in temperatures below 11ºF. Well before reaching this point, there will can be “noticeably longer boil times and difficulty lighting the burner with the built-in piezoelectric ignitor,” according to Jetboil. So you must intervene to warm the canister. Jetboil states that

“by keeping the canister warm before use, it is possible to use the stove with reasonable performance even when the ambient temperatures are at and below 0 Fahrenheit.”

So there is hope after all. Provided you can keep the canister warm, you should be fine on most winter backpacking trips in the Cascade Mountains.

The unfortunate temperature limitations of canister stoves are blurred by images of mountain climbers using canister stoves on snow-covered peaks. As Jetboil says, “We have had mountaineers use Jetboil stoves up to 8,000 m (26,000 ft.) on Mt. Everest and love them.” But snow alone is not equal to true winter conditions. Climbers rarely climb in the winter. The main climbing season, for example, on Mount Everett is in April and May, where average lows are in the lower 40s and highs in the 55–65ºF range. In those conditions, a canister stove should perform well enough. It is a different situation in the winter. You can expect low temperatures in the 5º–25ºF degree range during the winter months in the Cascade Mountains. If you don’t want to struggle to keep the canister warm, the liquid fuel stove is the solution.

“In the most extreme conditions, your best bet is a liquid fuel stove. The remote fuel bottle allows you to manually maintain the stove’s pressure in any conditions for reliable output.” —MSR, 2020

Reasons for Canister Stove problems

The performance of canister stoves depends on fuel pressure and flame efficacy. Four things affect the canister stove’s pressure and efficiency:

- Running the stove reduces fuel pressure. That’s right, the first cause of pressure loss comes from simply using the stove! As the stove runs, the fuel vaporizes cooling down the canister. The more pots of water you boil, the less efficient the stove becomes.

- Low fuel: The lower the fuel level, the more the stove struggles to sustain pressure.

- Cold temperatures reduce the pressure in the canister and at 11ºF the needed vapor converts to liquid. Altitude helps balance the pressure in canisters until altitude leads to cold temperatures, then this advantage is lost, leading to reduced canister pressure.

- Wind. “Even a 5 mph wind can cause as much as three times more fuel usage in a given cooking period.”

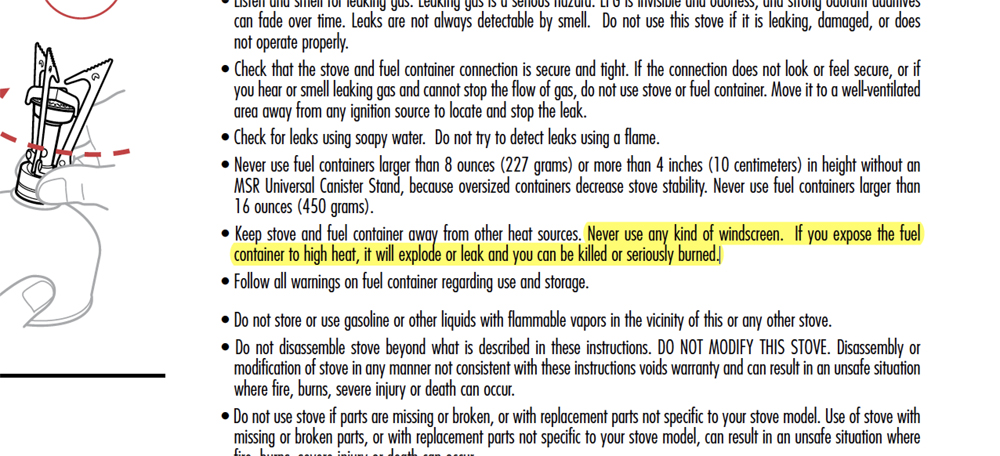

Bear in mind, the liquid fuel stoves have windscreens, but all manufacturers warn against using a windscreen with canister stoves, except for canister stoves that have a remote side attached canister, such as the MSR Windpro 2 or MSR Whisperlite Universal.

Bring extra fuel

You will use more fuel in winter. Avoid taking the minimum amount to save weight. If you’re on a 1–2 night trip have two full canisters of fuel or if you are using a liquid-fuel stove, bring a full 20-ounce fuel bottle. Fuel consumption will depend on how cold it is, how much snow you melt, how many meals you make and hot water bottles you make. Usually, you’ll be chatting in the cook area in the evening and drinking miso or tea and putting hot water bottles inside your jacket. We have had as many as four hikers show up on one trip without enough fuel.

Windscreens can be dangerous on canister stoves

The windscreen used on liquid fuel stoves surrounds the stove to protect the flame. The fuel bottle is outside of the screen, as it should be so as to not overheat the bottle and cause an explosion. All canister stove manufacturers warn against using a windscreen.

“Be advised, an actual metal windscreen is not recommended for propane-based canisters, as this can increase the potential for an explosion!”

Solutions to Canister Stove Problems

Stove designers have developed ways to mitigate these performance challenges.

- Built-in wind protection: The MSR Reactor, Windburner, and PocketRocket Deluxe have design features to help protect the flame from wind.

- Fuel pressure regulators: The MSR Reactor, Windburner, and PocketRocket Deluxe have Fuel pressure regulators. This regulator allows the stove to operate efficiently at a sustained low pressure. (More here: https://www.msrgear.com/blog/technology-stove-pressure-regulators-work/)

- Isobutane fuel: Isobutane canisters work better in cold weather than butane canisters. Isobutane is usually a mix of 20% propane and 80% isobutane. Brunton, Gigapower, MSR, Primus, and Snowpeak all use Isobutane canisters.

In addition to these design solutions, there are additional operational solutions, such as ways to warm the canister—putting it inside your jacket and protecting it from wind by building a rock or snow wall.

Inverted canister design solution

As mentioned above, at 11ºF the Isobutane vapor converts to liquid causing the pressure to drop off. Some canister stoves are designed specially so that the canister can be placed in an inverted position, allowing the fuel to continue to flow. That is, if the canister is inverted, the fuel flows out as a liquid. The MSR WhisperLite™ Universal, MSR WindPro™ II, and the Optimus Vega allow for inverted canisters. So how well does this work?

According to Optimus, “The Optimus Vega roars past its competitors that gasp and wheeze as soon as the temps go down. Colder than 0°C [32ºF]? Just invert the gas fuel cartridge using the integrated stand so you deliver liquid fuel. You can keep the soup going down to minus 20°C even! [-4 °Fahrenheit]”

That’s likely to be good enough for most winter trips in the Pacific Northwest.

Canister Stove Advantages

At this point, one may wonder how canister stoves became so popular. Climbers tend to find themselves in situations where they need to plan for colder conditions, but most hikers try to avoid cold weather. If you are not hiking in cold weather, canister stoves have two advantages—most are lighter and much easier to use.

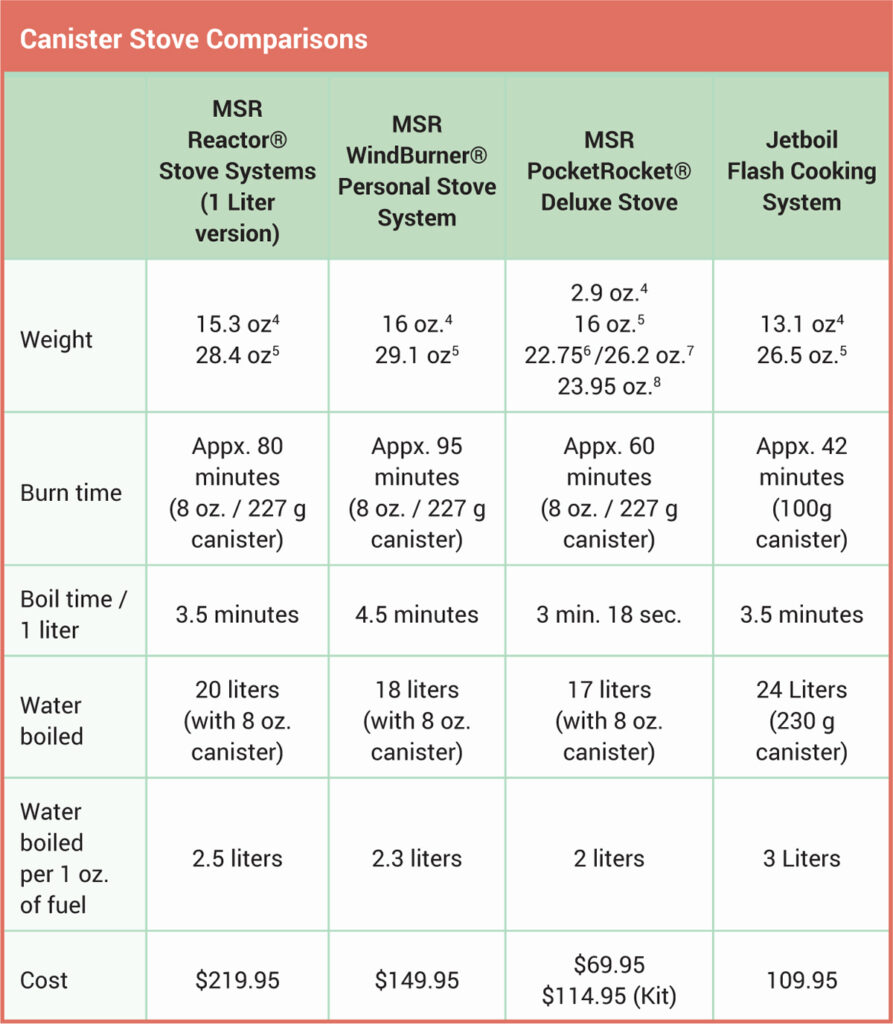

Weight

If it were not for the canisters that cannot be reused, I would consider a canister stove for warm-weather trips. The MSR PocketRocket Deluxe is, for example, only 3 ounces. The BRS-3000T stove weighs even less than an ounce. By comparison, the Whisperlite International weighs slightly over 11 ounces. Even though some canister stoves are much lighter, once enhanced features are added for cold weather, the weight differences are not so large. That is, the canister stoves systems that work best in the cold are more than a stove. They are cooking systems such as the MSR Reactor and Windburner, which include a windscreen and an integrated cooking pot. The custom design of the integrated cooking pot is critical for the stove’s performance. To compare a Whisperlite to a Reactor requires adding in a cooking pot to the weight of the Whisperlite. In the end, the Whisperlite system does end up being heavier than the canister options.

Ease of Use

Many canister stoves have piezoelectric lighters. You only have to push the switch to ignite the gas. The Piezo switch fails in cold weather, but you can use a match or lighter, so be sure to bring a reliable firestarter. All-in-all, the canister stove is very simple to understand and operate. Attached the canister, adjust the value and push the igniter.

A liquid fuel stove is more compilated. The Whisperlite, for example, involves attaching a fuel container and pump, pumping up the pressure, opening the valve to let the fuel bowl fill, and then igniting the fuel manually with whichever firestarter you prefer. This is a more complicated process and along the way, it is possible to under or over pump the pressure or leak out too much or not enough fuel. The fuel container must also be in the correct position with the adjuster value pointing up, if not, the pump may not reach the fuel in the container when the fuel is low. It is not that complicated, but it is not as easy as a canister stove. It is kind of like comparing manual shift cars to automative transmission cars. There is a learning curve.

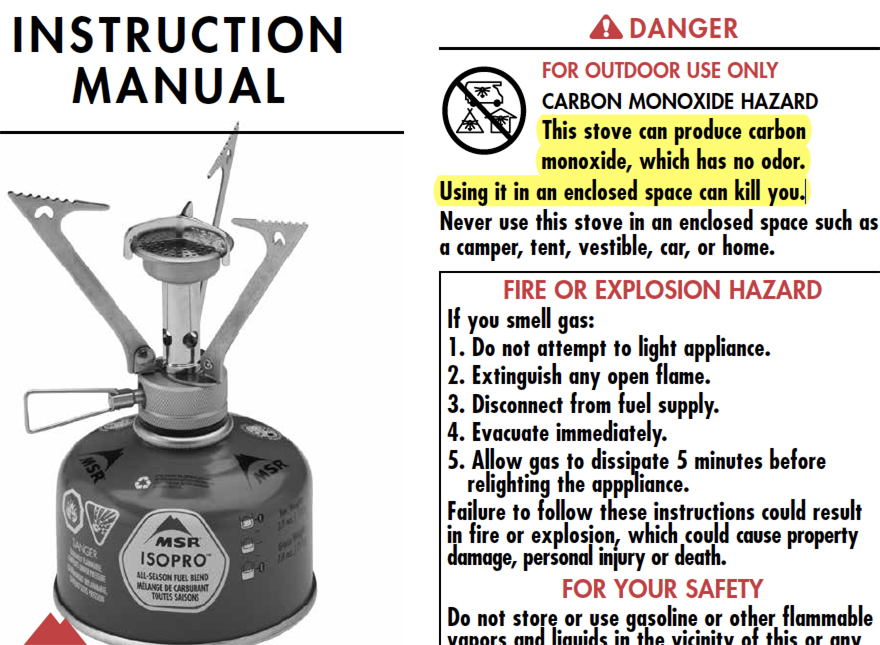

Stove safety

In theory, the most desirable convenience of canister systems is the ability to ignite the stove in a tent vestibule without having to contend with a large primer flame. That said, for safety reasons, I would not use a stove in a tent vestibule. If you take that risk, please take care that fumes are not entering your tent and the vestibule is open or well ventilated.

On a liquid fuel stove, the fuel pump causes fuel to flow into a primer bowl, which you manually light. This fuel creates a large flame that heats the fuel coil. The hot coil vaporizes the liquid fuel passing through the coil and creates the blue cooking flame. The initial primer flame can be large, so I never ignite my stove in my tent or near anything that could melt or catch on fire. I always operate the stove out in the open.

I usually dig a large cooking pit in the snow or, on very windy days, a small hole in the snow outside the door of my tent. It is in these sometimes harsh conditions that I understand why some hikers take the risk of using a canister stove system inside a tent vestibule. Because of the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning, I’m resigned to keeping my stove outside my tent. I carry some backup food that doesn’t require cooking when I encounter conditions too severe for my stove. Usually, even in cold and high winds, I can keep my body protected in my tent while operating the stove outside the tent door.

Carbon Monoxide (CO) Poisoning

Be very careful about carbon monoxide poisoning. When the weather is cold and windy you’ll be tempted to use your stove in an enclosed tent vestibule. The CDC advises against using any fuel-burning device in a tent. If you use a ventilate for your stove do not seal it up! Using a stove in a tent vestibule is also dangerous. The deadly fumes are odorless and have killed hikers and climbers. This is a real danger and if you search the topic there are many tragic stories and statistics. Some symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning are similar to the less dangerous altitude sickness. More here.

Be careful about carbon dioxide (CO2) levels too

Even aside from using a stove in a tent, care should be taken to prevent Carbon dioxide (CO2) levels from reparation in an enclosed tent from rising too high and creating an oxygen-deficient atmosphere. Let your tent breathe at night. Leave the door open or partially open when you can, and be mindful about clearing away snow buildup that can block ventilation. I almost always sleep with my tent door and top vent open even with a double-walled tent that breaths well.

Let me know your thoughts. If you have tips for how you keep your canister warm in winter or success or failure stories in cold conditions, let us hear your experiences. Please leave comments below.

7 replies on “Will a Canister Stove Work for Winter Backpacking?”

This was really useful information, thank you for providing it. I’m willing to camp down to 25F. I used a liquid fuel stove for years and just last year switched to canister because it is lighter and less of a hassle to light. I don’t think I’ve experienced anything less than 34F with it. Having read this I’ll keep my fuel in my sleeping bag with me and perhaps my water bottle and fill my dog’s water bowl with that water when the temperature dips.

I’ll probably continue to use canister until it fails me, then I’ll buy some liquid fuel and get my previous stove out.

Thanks Jason. Glad the article was useful. I recommend using Nalgene bottles in sleeping bags, and if its hot water, retightening the lid about 10 minutes after closing it because the lid will slightly loosen as it begins to cool. Just be aware that after a second tightening, it can be hard to open in the morning.

Another great article. So much useful information on this site!

I’ve never liked gas canisters, even for non-winter/three-season use. Having to throw away empty canisters, and one never really knows how much fuel is left once the can approaches being empty… not appealing.

I use an alcohol stove most of the time now, and a liquid-fuel stove in winter.

When i took the Appalachian Mountain Club Winter Hiking Class a few years ago, i went out with folks who used the butane/iso-butane cans. Here in the northeast (White Mountains in N.H. and Green Mountains in Vermont), winter low temperatures can drop to 0ºF (or below, in which case i stay home), so standard procedure for canister-stove users seems to be keeping the can in a pot-lid or tray with an inch or so of tepid water, which seems to solve the problem. When melting quantities of snow, and the stove is running for a while, the water needs to be occasionally renewed with warmer water.

A clever hack, which i haven’t actually tried yet (bought the copper, waiting for cold weather), is to affix a strip of copper to the canister, with the top of the strip just catching the flame, so some heat gets shunted to the can to keep it warm.

One example here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6HiTrgT-Dd0 (Butane Canister Stove Winter Hack – Running Below 20°F – moulder strip)

Given that i still won’t like canisters even if this hack works, most of the time, i’ll still be sticking with my 40-something-year-old Svea 123. (It’s okay, you can chuckle.)

With a little less heat output, it’s slower than a Whisperlite (but not much), and it’s never failed in all these years. Yeah, it can be a little finicky to start, but it’s really just a matter of preheating the fuel tank with some fuel or fire paste and waiting out a minute or so of sputtering until the tank get up to operating temperature. I’m generally not in that much of a hurry.

I use to use a Svea stove too! Amazing stoves, and cool that they still exist. I have very fond memories of it. I have heard a number of cold-weather canister techniques, such as rotating canisters under one’s armpits, but I can’t see the appeal. I have heard about the harm-water technique, but how it can work is a mystery. Where’s the water coming from? Usually, there is nothing but snow all around and there’s no water until the stove melts the snow. I have not tried an alcohol stove, and I would be skeptical except Eric Normark uses one. If you have not heard of him, check out his videos on YouTube. He does super beautiful films (example https://youtu.be/LW2tzyWvHMI). He uses skis, a pulk, and builds fires, things I don’t do, but he is usually on flatter terrain where a pulk makes sense.

For the butane canister-stove water bath, one simply scoops or pours a bit of the heated water out of the snow-melt pot once it heats up, and adds it to the water-bath pan to maintain a warm-ish temperature. For the first firing, i think people just tuck the canister under their jacket for a while doing camp set to warm it up a bit.

Alcohol stoves work fine for three-season use, but don’t have the heat output needed for snow melting in an efficient way. Opinions vary as to the best fuel for these, but denatured alcohol is a good bet, and is available in most hardware stores. There are all kinds of plans for DIY stoves, but i like the Trangia with a pivoting gate/cover that allows for dialing down the flame somewhat for simmering. Also have a Mini Bull Designs/Tinny stove that is tiny and light.

Big fan of Erik’s meditative videos. He has access to some spectacular landscapes in Northern Sweden.

The story behind the MSR Reactor. It is an excellent stove for melting snow and boiling water. I only use it in the winter. Also it doesn’t work well at all for simmering.

THE ORIGIN STORY OF MSR’S REACTOR STOVE

https://www.msrgear.com/blog/the-origin-story-of-msr-reactor-stove/

Thanks Patrick. Most people in our group are using the Reactor or Jetboil on our trips and doing okay until around 15ºF or below, at which point it becomes more challenging. I still prefer the Liquid-fuel stove.