Winter backpacking is much safer if you are in a group but how do you find other people interested in this activity? If you live in Washington State, join our winter backpacking Meetup. If you live elsewhere, the tips outlined here are for you.

This information is intended to help you find other winter enthusiasts and build a winter backpacking group where you live. There are many ways to go about growing a backpacking group. The suggestions offered here are based on the history and experience of our Pacific Northwest group.

Starting with Social Media

Some hikers use Facebook, Meetup, WhatsApp, and WeChat to organize events and share photos. Other platforms may also work. I mainly use Meetup and WhatsApp. The easiest to use are perhaps Facebook and Meetup. You simply search these platforms for hiking groups nearby and/or create your own.

Our group is based in Washington state. The mountains and forest are not far away and people living here want to get out and enjoy abundant natural beauty. Hiking, backpacking, and climbing have a long history in the state. The state has 31 designated Wilderness Areas and is home to Mount Rainier, Olympic, and North Cascades national parks. It also has Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, 3 national recreation areas, and 8 national forests. The Mount Baker–Snoqualmie National Forest alone extends 140 miles from Canada to the boundary of Mount Rainier National Park. All of this outdoor wilderness, parkland, and forests, has helped create an outdoor recreation culture in the state.

Be Patient

Even with around 12 million Washington and Oregon residents and the 24 ski areas claiming 4.5 million ski visits in 2022–23, it is still hard to find winter backpackers. It took about 6–8 years to build up the group to a level that can do events nearly every two weeks of the year.

This should be possible in other states too, especially ones with large wilderness areas and existing hiking communities, such as California, Colorado, New York, Utah, Wisconsin, Michigan, West Virginia, Georgia, and many other parts of the world.

It takes time because you need to have enough winter events and participants for word to spread.

Build Friendships in the 3-season Hiking Community

Initially, I met other backpackers by joining hiking Meetups in the Seattle area. The largest hiking Meetup in the Seattle Area is Seattle Outdoor Adventurers which has 27,000 members and around 80 organizers. I have heard the Sierra Club in Los Angeles and Orange Counties represents 43,000 members and that the Los Angeles Hiking Group has 15,000 members. The Colorado Mountain Club (CMC) is considered the largest hiking group in Colorado with 10,000 members. There are similar large hiking groups in New York and New Jersey. Michigan has the Hiking Michigan Welcome organization. Wisconsin has the Milwaukee, has three growing hiking groups. Idaho has the Idaho hiking Club and a hiker who moved from our area to Idaho stated the Utah Hikers and Backpackers Meetup. If there is no hiking group in your area you can start one.

I joined different Meetups but eventually found Hike to a Summit which had around 1500 members. This Meetup had a core of maybe 100 devoted 3-season day hikers. They did hikes exactly as the name implies. They would hike to a summit to enjoy the views and then hike back down the same day. Their Meetup changed hands several times before the main organizer moved away. After that I used the Meetup to organized overnight backpacking trips.

Hike to a Summit was a good Meetup for day hikers, but it became clear that few people in that Meetup were interested in overnight backpacking, and fewer were willing to go backpacking in cold weather. Day hikes are fine, but I want sunsets, star-filled nights, sunrises, and winter landscapes. Different Meetups and organizers emphasize different types of events and attract people with different interests. Some do short day hikes, some overnight trips, some scrambling and climbing, etc.

The Winter Backpacking Meetup

Wanting to find more people interested in winter backpacking, I decided to start a new Meetup called Winter Backpacking in the PNW, which I later changed to simply Winter Backpacking. This name allowed people to understand the emphasis was on winter activities such as snowshoeing and overnight camping. The App allows me to share photos that indicate that we are doing snow activities and not trying to find low-elevation lakes and rivers where most people go in the wintertime.

For years the group was small and I often had to cancel events because too few people signed up. This all changed with the COVID-19 pandemic. As the Pandemic ended, people were eager to get back outdoors and membership suddenly grew. Most important, word about our group was spreading in the hiking community. Another hiker agreed to help and having two organizers improved the experience for people attending. More people signed up for events and some events reached the 12-person limit.

The Winter Backpacking Group Page

In 2021, I started a Facebook group page. The purpose of the Facebook group page was to allow people interested in winter backpacking to share their experiences and photos from around the world. The group page has nearly 3000 members but low participation which is why I’m sharing these tips for how to organize a winter backpacking group.

There are many Facebook group pages for hikers and backpackers. In our area there are the Washington Hikers and Climbers, Mountain Loop Highway Hikers And Backpackers, PNW Washington Hiking Group, and many more. Individuals use these group pages to find other hikers and share information such as road closures and trail conditions.

In addition to Meetup and Facebook, WhatsApp is a useful tool for event planning. The messaging feature on Meetup is unreliable. People are not always seeing the messages, but they are more responsive to WhatsApp messages. I don’t always use WhatsApp, but if people sign up for an event that involves more planning and coordination, I invite them to join a WhatsApp chat group to discuss the planning. These discussions include permit information, who is carpooling, shuttling if the final trailhead is different from the starting point, gear requirements, after-hike restaurant options, and so on.

I also created this website, WinterBackpacking.com, to explains the gear and skills needed for winter backpacking in the mild and often wet conditions of the Pacific Northwest. Every person joining the Meetup receives a short welcome letter discussing the liability release, basic gear requirements, and further reading on WinterBackpacking.com.

I share photos and videos on Instagram and TikTok to let people see what the events are like. Apart from using social media, I do not do any advertising or promotion. All events are free except for costs such as transportation and permits. Most events don’t require permits.

Why I Don’t Monetize

If you’re wondering how I monetize winter backpacking, the answer is, I don’t. It cost me money, such as the Meetup subscription fees and the cost of hosting this website, but it is what I like to do. I encourage others to approach it in the same way. The benefit to you is all the wonderful wilderness experiences you get to have and all the people you meet. Likewise, I review gear on the winter backpacking website, but I don’t represent any brands or receive any payments. I want people to know that the reviews can be trusted.

Ask for Help

Hiking groups often split into fast and slow hikers. New hikers can struggle with balance in deep snow and are sometimes filled with anxiety and fear making mistakes or being left behind. As an organizer, it is hard to look after new hikers, slow hikers falling behind, new hikers getting too far ahead and also keep the group together, and be upfront navigating to the planned destination.

If you can identify a person who can assist you with the organizing, it will make it easier to keep the group together. Enlist a capable hiker to help you. Someone who will help you reign in the ones that want to take needless risks. Explain that you want them to consult with you and help keep the group together. Be encouraging. Two heads are better than one. It is good to give everyone a voice in the group, but ultimately, decisions need to be made. If you can make the decisions with another respected hiker in the group, it is easier to maintain group unity and safety.

Prioritize Safety

Winter backpacking in groups is safer than going solo. Groups are a great way to share knowledge and practice safety skills. If you are starting a group, be aware of the hazards and gear requirements, some of which may be unique to your destination and weather conditions. The trails are often hidden under snow along with streams, frozen ponds, and tree wells.

- Everyone should have avalanche gear and beacon recovery skills while exploring mountainous terrain.

- Use routes on slopes anchored with trees and rocks. Make ascents on approaches with less than 20–25º inclines.

- Choose campsites in open spaces away from snow-loaded trees or slopes.

- Pack a kit that doesn’t require fires for warmth and exceeds the demands of the weather forecast.

- Have wind-protecting gear to prevent hypothermia and frostbite.

- Pack in gear redundancy and ensure everyone is self-sufficient if separated from the group.

These are just a few important safety considerations. With the appropriate gear and skills, winter backpacking can be a comfortable, unique, and amazing experience.

Build a Group Safety Culture

For more about building a group safety culture, click here to learn about the following:

- How to Build a Group Mindset

- Vetting Members

- Create a Measure of Fitness

- Types of Gear Checks

- Communicating with New Attendees

- Managing Expectations

- Encourage Self-sufficiency

Have a Liability Release

If you want to limit your liability you may need to seek professional legal advice—something I can’t offer. Liability is a serious concern. For every event I plan, a Release of Liability is posted in the event description and I request an acknowledgment that participants are releasing the organizer from liability. Everyone is informed in the Welcome Letter that joining the Meetup means that they are accepting of the Release of Liability. Some organizations are stricter and require a signed document, such as the Sierra club.

- Avoid charging or accepting any payments because that may be interpreted as indicating you have a fiduciary duty.

- Make it clear that everyone is responsible for themselves and for knowing the risks they are accepting.

- Never understate the dangers or risks involved.

- Never characterize a route or activity as “safe.” Any hike into the mountains, any time of the year, involves hazards that could result in injury or death.

- Encourage people to join, but make it clear that the dangers and hazards are real and are part of the experience.

Be Inclusive

The goal is to increase safety by building a team and that’s easier to do if you have an inclusive mindset and strategy. It is best to set aside assumptions about who will be interested in winter backpacking or capable of doing it.

When it comes to carrying a heavy pack up a mountain, I have not found that large men are better at it than small women. Often when I post a difficult hike, it is mostly women who sign up. Some members are experienced mountaineers and others are office workers just discovering outdoor recreation.

Neither gender nor age are indicators of ability. Many of the strongest and most capable hikers in our meetup are small and in their 50s and 60s. Many of the slower hikers are better able to reach the destination on longer routes. The general guideline is that a backpack should be no more than 20% of a hiker’s body weight. For the smaller hikers in our group, it is closer to 30%. You cannot judge a person’s abilities or commitment by appearance.

My own observation is that Meetup groups that are more inclusive tend to have more participation and longevity.

Creating a safe and welcoming Meetup experience is not difficult. Here are a few basic tips:

- Avoid gender assumptions.

- Avoid comments about a person’s appearance.

- Avoid comments and jokes about sex and sexuality.

- Don’t over-explain. Before offering advice, consider prefacing it with “I would like to offer some advice but I don’t want to be explaining something you already know.” They will appreciate the respect and usually indicate whether you should proceed.

- Let people take care of themselves. Don’t touch or give physical assistance unless it is requested.

- Have a three-person minimum.

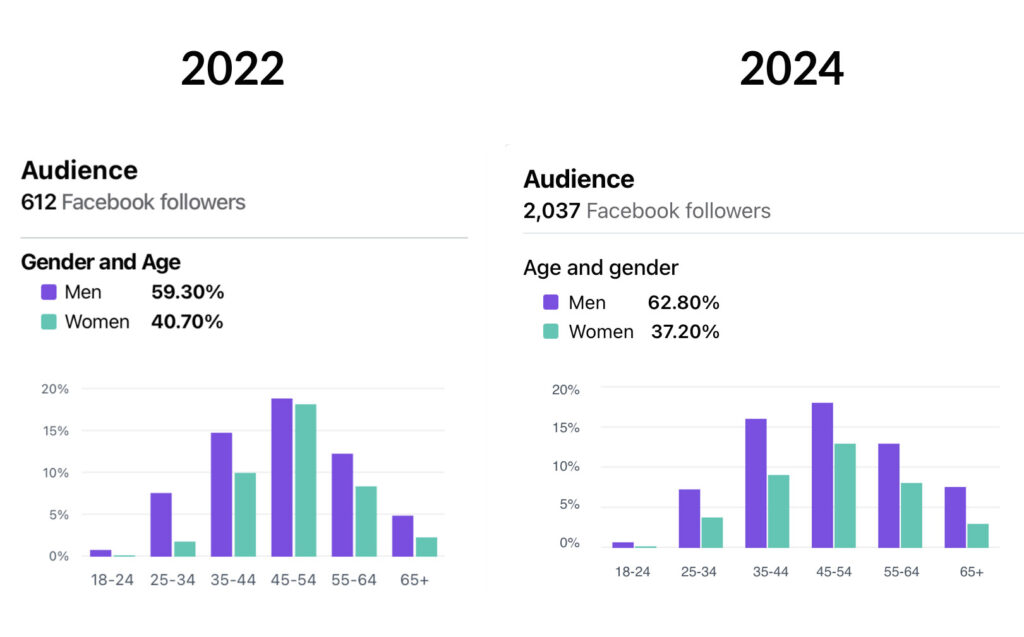

Some of our events are majority-male and others are majority-female. The membership stats for our Facebook Group page are about 60/40 male/female with the largest number of hikers in the 45–54 age demographic. For some reason, it seems that people are more adventurous in that age group.

Friendships

In 2019, my closest friend and teenage hiking buddy passed away from a heart attack in his sleep. I have thought much about the value and importance of friendships following this loss. In particular, how our backpacking group can help people discover and build friendships through shared experiences. Friendship can be an important source of joy and support in the course of our lives. The best kinds of friendships are the ones that encourage us be our best selves.

Are you familiar with the Harvard Study of Adult Development? It is the longest in-depth study on human life ever done, with the researcher concluding that good relationships is the most important thing leading to health and happiness. “The trick is that those relationships must be nurtured.” The current directors, Waldinger and Schulz authored a book based on the findings, The Good Life: Lessons From the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness (2023). The book presents the research findings and also contains tips for maintaining relationships. For example, they discuss how we may withdraw from others or lash out when conflicts arise in relationships. “Neither of these are ideal ways to manage stress or anger, as they aren’t focused on preserving closeness or working through difficulty.” The authors suggest that, “The key is … a more considered and purposeful response that aligns with who you are and what you are seeking to accomplish.” They point out that this can help you be less reactive and give you a better chance of working through issues. And what are we seeking to accomplish? Friendships.

Seattle, like most American cities, is a diverse place with people from around the world. This diversity is reflected in our Meetup group. We have hikers ranging from early 20s to mid 60s from China, Taiwan, India, Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Latvia, Israel, Syria, Iran, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Germany, France, Netherlands, and more. Thankfully, the people who join in our activities are openminded and accepting of diversity.

Many are already experienced backpackers and others are new to the activity. People from every background enjoy winter backpacking. Don’t assume any particular ethnicity, gender, or age group will not be interested in winter backpacking, capable of handling the challenges involved, or unable to be your friend.

People are individuals and everyone loves the wilderness in their own way. My own experiences with winter backpackers has confirmed my belief in the fundamental oneness and goodness of humankind. I am grateful for all the people who have joined in on these wilderness adventures.

Be Mindful of the Cost Barrier

One barrier that cuts across gender and ethnicity is costs. Because winter backpacking requires a larger investment than 3-season backpacking there is a tendency for some people to not participate even though they are interested. Worse, some hikers will omit gear that is important for safety because of the costs.

If I had to buy new winter gear, using my current recommendations for just the top ten items, the cost would be around $2,800 (without tax) and that’s with some items on sale. Some people will spend more for a bicycle or a hotel on one vacation, so comparatively, it is not much costs and the gear can last for years. Nonetheless, the costs will inhibit some people, especially if they are unsure if they will enjoy the activity.

Examples of gear prices (2024)

- 4-season solo tent (Leipen Air Raiz 1) $332

- 60-liter backpack (Granite Gear Crown 3): $181 (sale price)

- Sleeping bag (Thermarest Parsec 0ºF): $341.97 (sale price)

- Air mattress (NeoAir XTherm NXT): $239.95

- Down jacket (Phantom Alpine Hooded Jacket): $449.99

- Mountain-terrain snowshoes (MSR Evo™ Ascent Snowshoes): $239.95

- Avalanche transceiver (Black Diamond Recon X): $349.95

- Hiking boots size-fitted for winter (Camino Evo GTX): $349.95

- Liquid-fuel stove (MSR Whisperlite Universal): $199.95

- Expedition-level mittens (Outdoor Research Alti II Gore-Tex): $98.83 (sale price)

Total: $2783.54

Like many activities, it is possible to start out with low-cost gear and upgrade later. For my first trip, I used a heavy synthetic zero-degree sleeping bag that cost less than a hundred dollars.

Be mindful of the cost barrier. Avoid creating a culture where people feel unwelcome if they don’t have the best name brands or most expensive gear. Some hikers are good at making 3-season tents work in winter conditions. There are hikers who participant regularly with gear I wouldn’t choose. As long as they are safe and it works for them, it’s okay. The goals are safety and participation.

Because gear costs can be a barrier, it is useful to keep some extra gear around to loan out. Most importantly, I have two extra transceivers. Beyond that, I can outfit someone with a complete kit if necessary. If they have a good experience, they will likely get the necessary gear and come again. There are few things more satisfying than introducing someone to an activity that has such high rewards and enjoyment.

Offer Events for Beginners

One way to encourage participation is to offer a range of events, some easy enough for beginners and some that require less gear commitments. I have two main types of events for beginners. At the beginning of winter, I plan short snowshoe trips to an area near a ski resort. This allows beginners to try out their gear and learn techniques from more experienced members.

At the beginning of summer when there is still some snow to camp on but the air is warmer, I plan several short hikes to introduce hikers to snow camping. This allows hikers to experience camping on snow without having to upgrade their 3-season kits. Fear of camping on snow is one of the biggest barriers to people participating. Giving hikers this basic skill enables them to get over this fear.

Planning events in the spring, summer, and fall, also allows new members to meet members who have experience in winter conditions. This process of building relationships in warm-weather conditions encourages new members to join for the colder events.

Guard Your Group Reputation

As I mentioned earlier, it takes time to build up a Meetup and for word to spread around the hiking community. Reputation is important. People need to hear that the group is a safe space and welcoming. People accept that the mountains can be dangerous but they don’t want to be harassed by other hikers or feel unwelcome. It is up to you as the organizer to create a positive and inclusive culture. A successful Meetup is a real joy, don’t let anyone or bad behavior spoil the group reputation.

Let us know your thoughts and suggestions

The path that led to our winter backpacking community is one way to do it. Perhaps you know some additional or better ways. Please share your ideas, experiences, and challenges below. Your comments and questions are welcomed.